History of Propaganda Magazine

"Propaganda is probably the only subculture publication known to just about every goth on the planet."

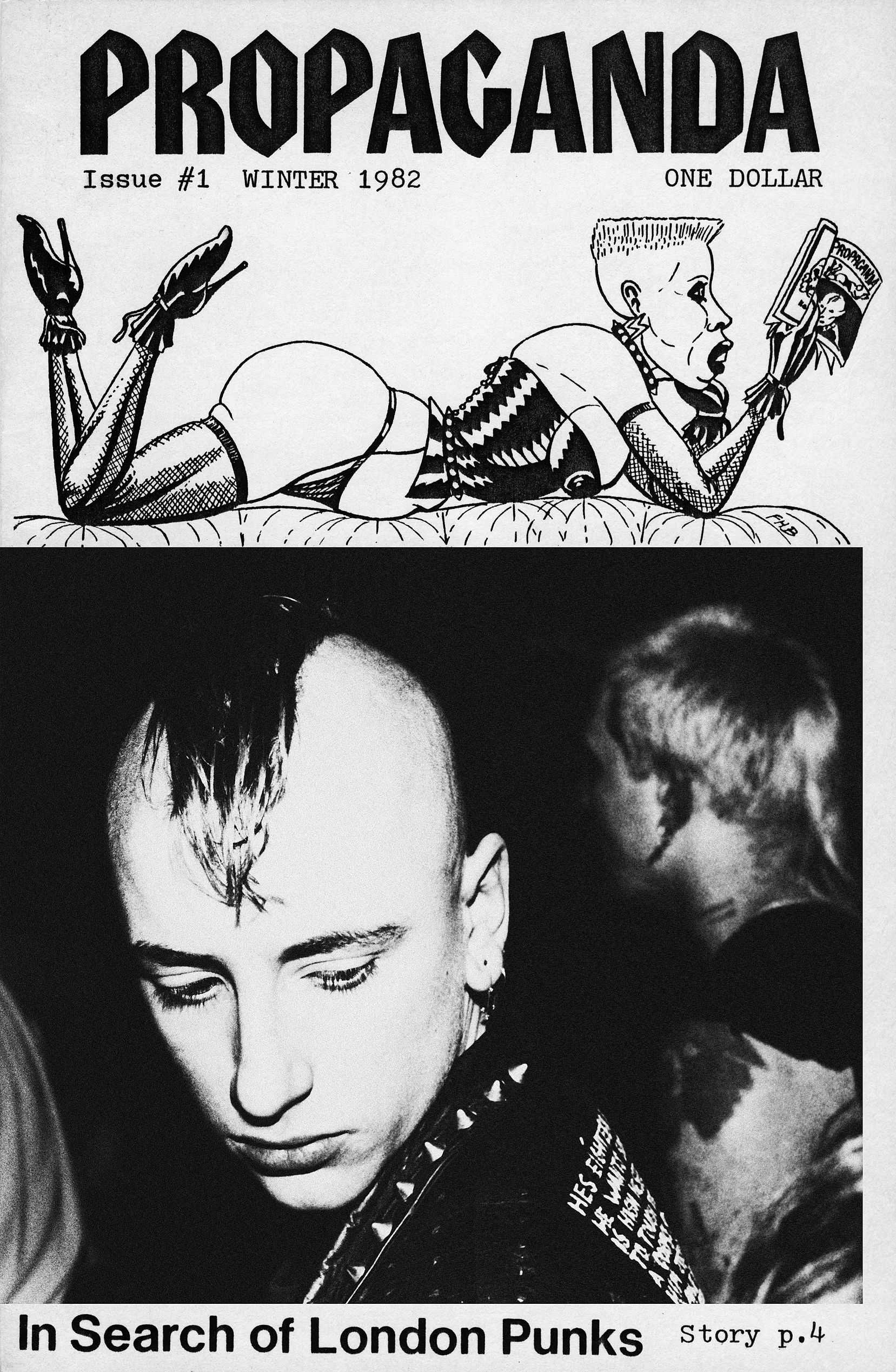

Amidst the maelstrom of the Lower Manhattan hardcore punk scene arose an audacious little fanzine emblazoned with the provocative title Propaganda. It was early 1982 and the Zine Revolution was in full swing, with intrepid young journalists like myself covering the action at nightclubs such as CBGB, the Mudd Club, A7, and the Peppermint Lounge. Braving the brutality of the mosh pit, I was determined to capture the mayhem up close, and even suffered a broken camera in the process. With bands like Fear, Black Flag, Flipper, and Bad Brains, as well as fierce street style, splashed across its stark black & white pages, Propaganda soon gained a reputation for editorial and photographic excellence.

Punk rocker at London’s Marquee Club.

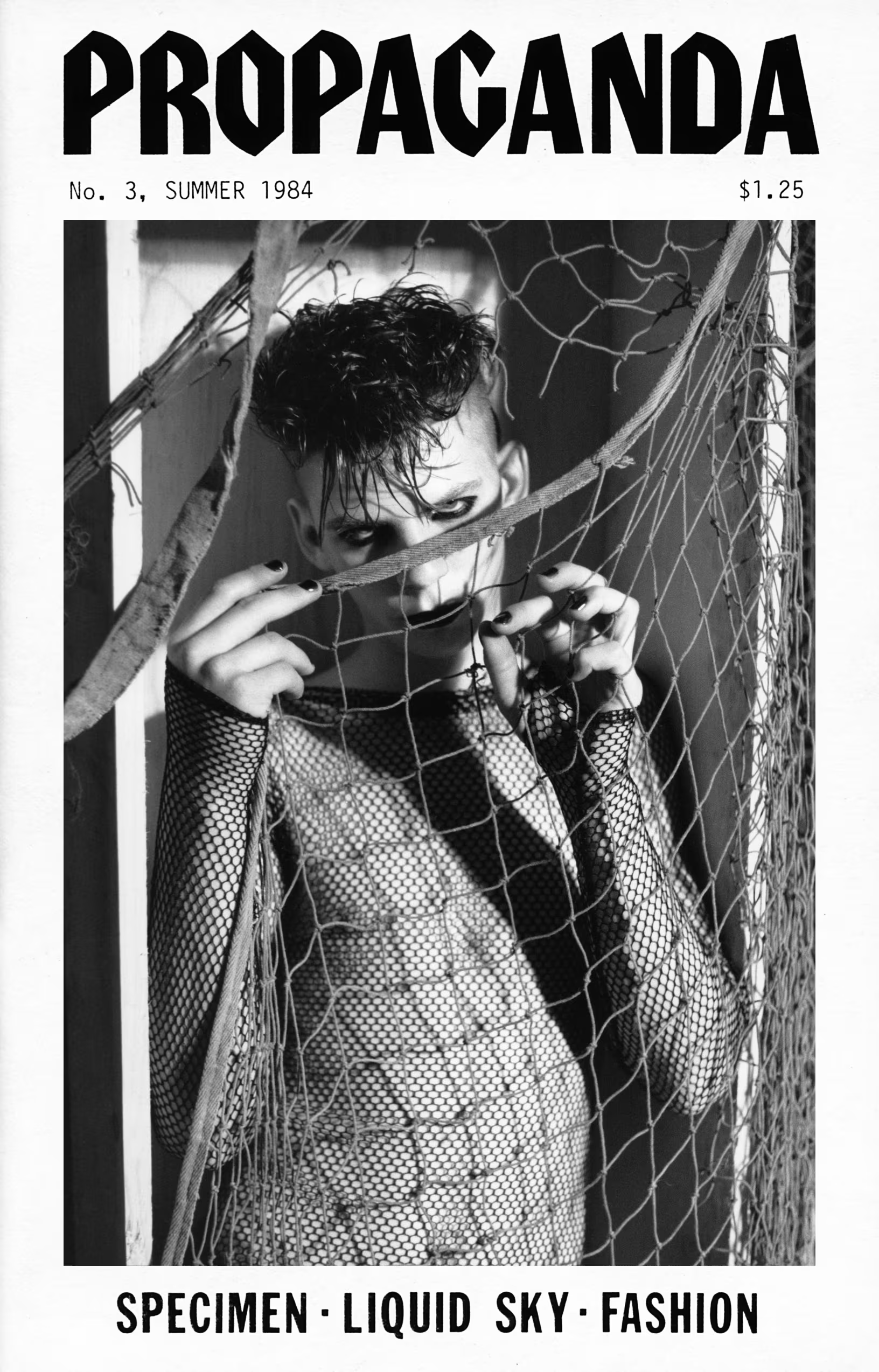

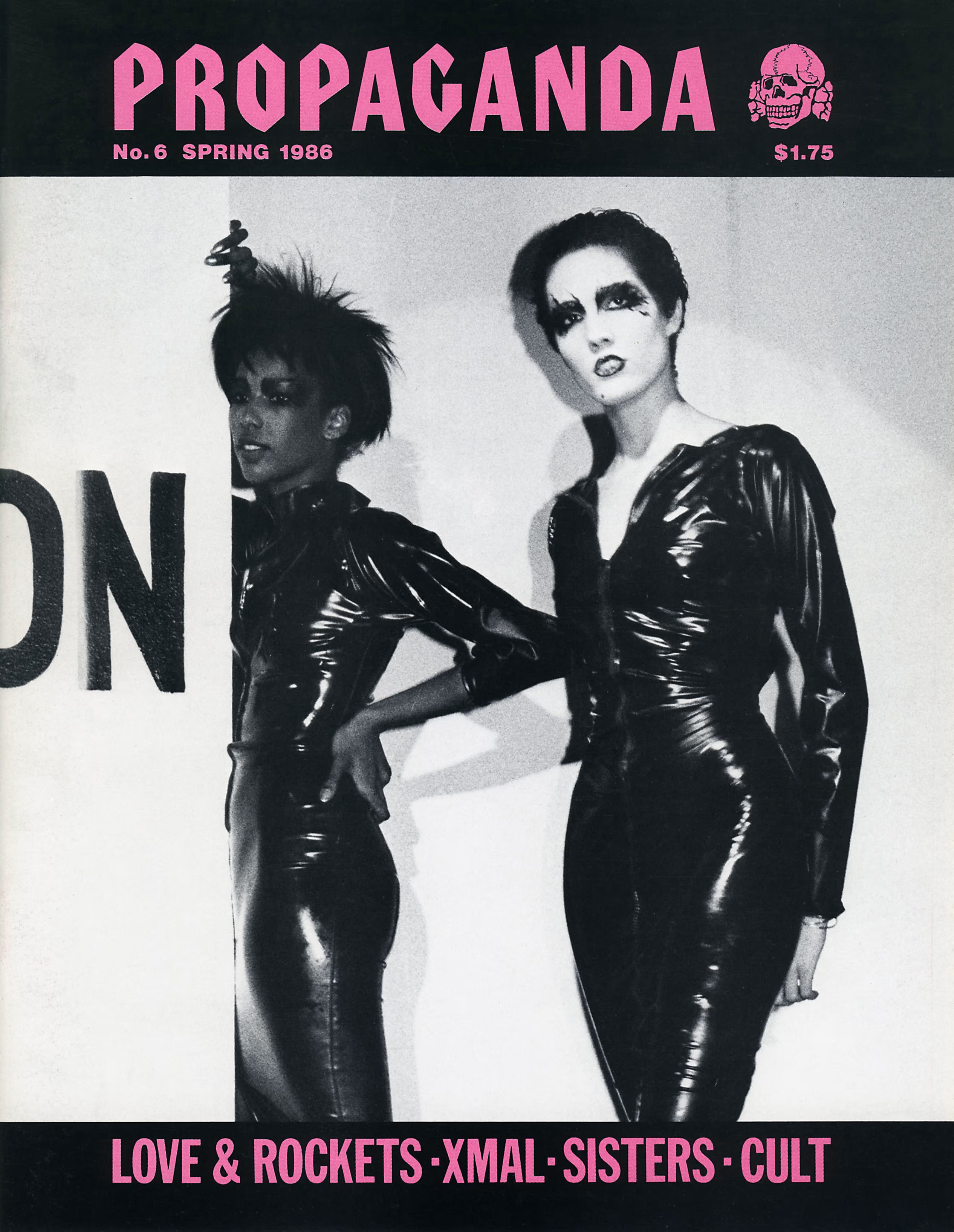

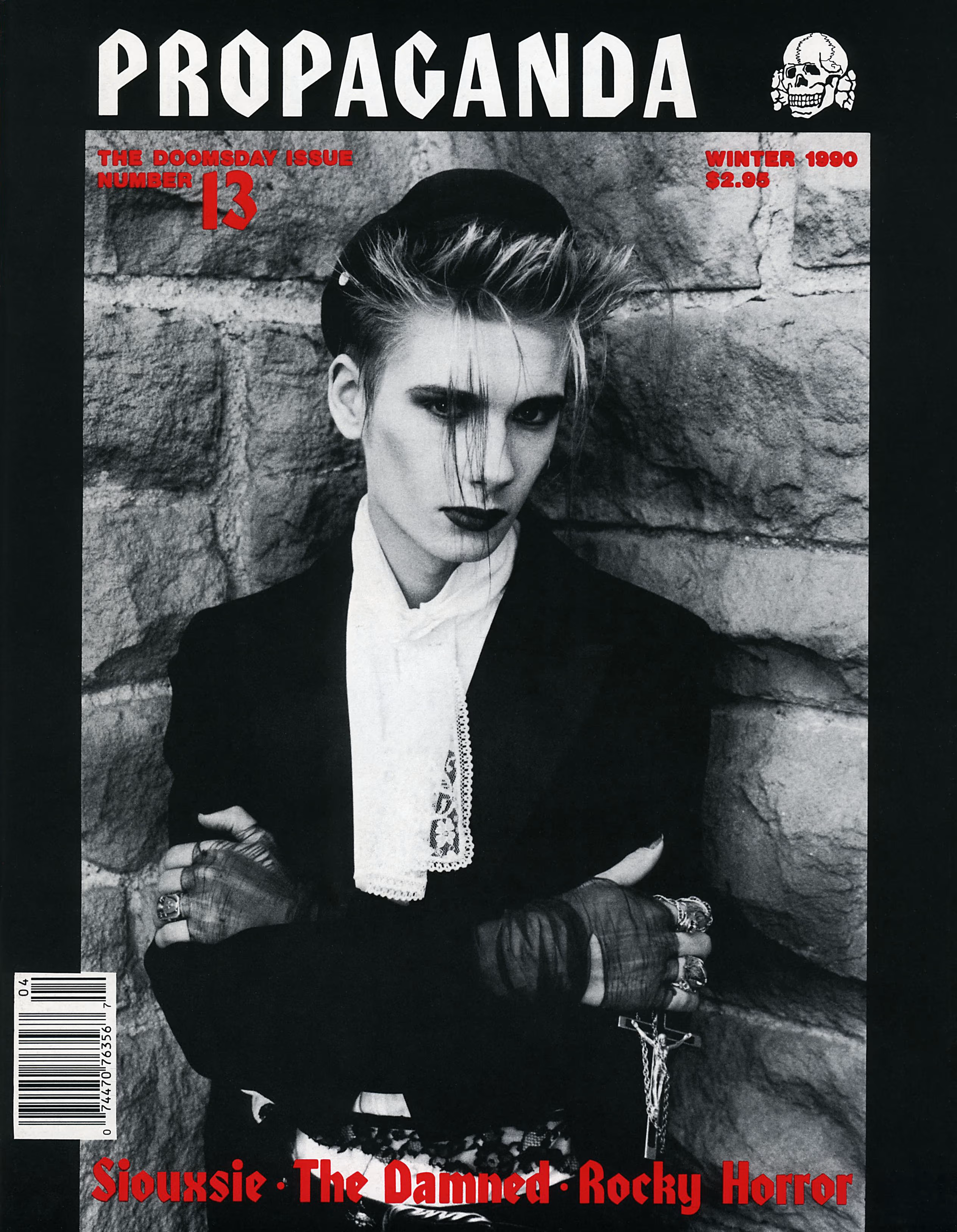

Despite its encouraging prospects, a rapid escalation in the scene’s mindless violence and self-destructiveness eventually convinced me to terminate the publication a year and a half after launching it. However, it gained a new raison d’etre when I discovered the band Bauhaus by way of the 1983 vampire film The Hunger. The group’s appearance in the opening scene absolutely captivated me, and the course of history was thus altered, with Propaganda subsequently chronicling the burgeoning gothic subculture. Centered primarily around Danceteria, the World, and the Cat Club in Manhattan, it proved to be an astonishing milieu replete with a bevy of undead beauties adorned in black leather, velvet and lace, who were just aching to be photographed. It was from these enchanting children of the night that Propaganda’s original supermodel, Rex, was recruited. Owing to his androgyny and versatility, he was a true chameleon of style and graced the covers of three different issues in the mid-1980s. At this time and towards the end of the decade, these clubs and others hosted The Sisters of Mercy, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Peter Murphy, Love and Rockets, Xmal Deutschland, The Specimen, Clan of Xymox, and Fields of the Nephilim, all of which were featured in the magazine.

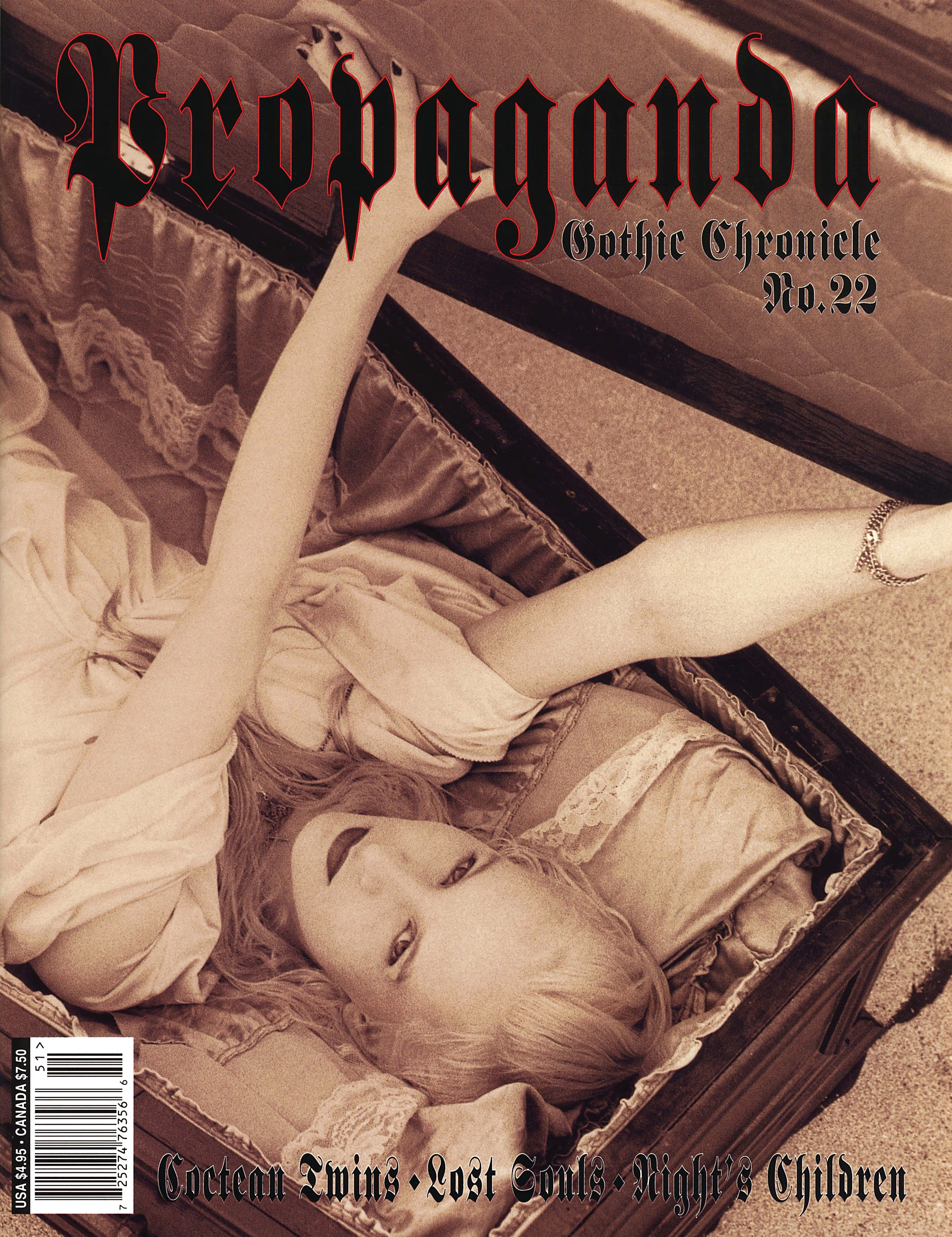

Cover model: Rex

In 1989, Propaganda’s focus shifted to the West Coast, with Helter Skelter in Los Angeles, House of Usher in San Francisco, and Soil in San Diego being especially noteworthy destinations on my journalistic itinerary. Helter Skelter in particular catered to an exceptionally theatrical clientele, whose fashion sense recalled the horror cinema of Hollywood’s golden age. It was here that I discovered the remarkably beautiful John Koviak, the bass player of the L.A. goth band London After Midnight. I spent the next three years photographing and filming him and making him a household name throughout Gothdom. His girlfriend Tia Giles, with her bride of Dracula allure, also made a name for herself as the magazine’s leading female model. From 1991 to 1994, a series of Propaganda film productions were released, with John starring as an inquisitor priest in “The Sacrifice” and Tia starring as an aristocratic vampire in “Blood Countess.”

Pure Sex latex fashion show at New York’s Danceteria nightclub.

The next region to receive extensive coverage was the Southeast from 1996 to 1998, with articles about the Chamber in Atlanta, Club Z in Orlando, and the Angel Club in New Orleans being published. I made repeated trips to the first two nightspots, each of which hosted Propaganda parties, with the graveyards of the Big Easy providing magnificent locations for various fashion shoots. It was at this time that I acquired my next modeling sensation, the quintessential Cajun goth boy Christophe Boutlier, whose dark sultry mystique made him an instant fan favorite.

Cover model: John Koviak

Another outstanding mannequin of the late ‘90s was Brooke, whose range of personas caused her to be perceived as several different male, female, and transgender models, with the covers of two consecutive issues displaying her best butch and femme looks. Throughout the decade notable goth, industrial, and darkwave groups came to Gotham, with Laibach playing at the Limelight, Shadow Project at the Pyramid Club, Diamanda Galas at Saint John’s Cathedral, and Death In June at the Angel Orensanz Center. All received prominent reviews with accompanying interviews. Such was the Propaganda modus operandi – an even mixture of music, fashion, and nightlife that set it apart from other genre publications, which reported almost exclusively on music-related topics.

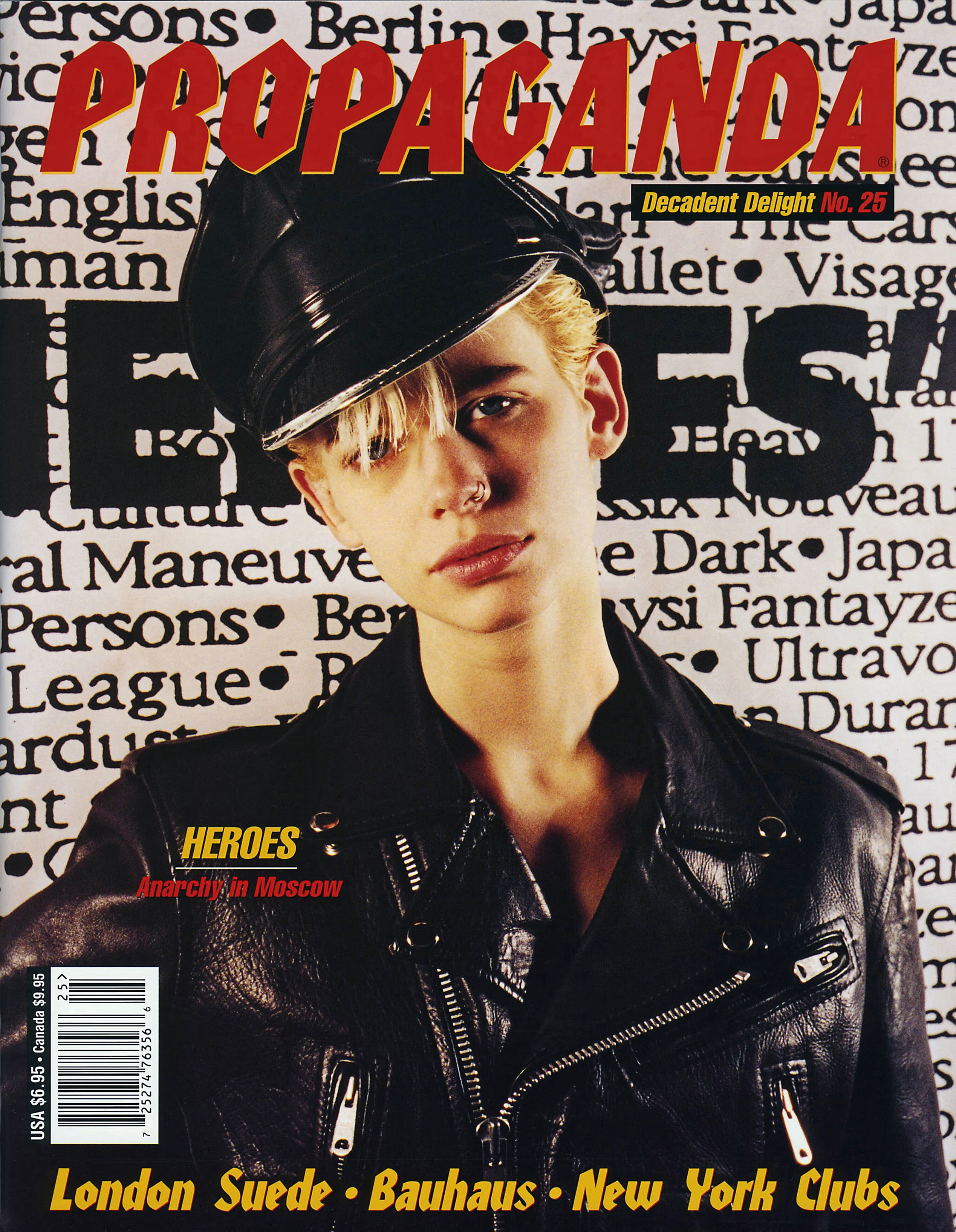

Cover model: Scott Crawford

Propaganda’s editorial reach expanded overseas to Japan, France, Germany, and the Czech Republic from 1999 to the release of its final issue in 2002, with articles on Tokyo street style, the Paris Catacombs, Hamburg’s fetish scene, and Prague’s alternative nightlife. This resulted in a substantial amount of international press lauding the magazine’s unique and compelling counterculture perspective. Its 20th anniversary party was held at the legendary Parisian rock bar Les Furieux, which also presented an exhibition of my most iconic photography spanning the magazine’s entire history from 1982 to 2002. With an unforgettable finale featuring the avant-garde performance art of Propaganda’s last cover boy Lui A., it was a worthy tribute to the world’s preeminent gothic journal, and a fitting note on which to bring down the curtain on this quixotic venture after its epic publishing run.

Cover model: Tia Giles

From a small Xeroxed fanzine with only a few hundred copies distributed in New York City, to a full-size glossy periodical with up to 22,000 copies per issue distributed nationally and internationally, Propaganda had come a long way from its humble origins. Carried by the top book, magazine, and record retail chains of the era, from Barnes & Noble and Borders Books to Tower Records and Virgin Megastores, its influence could not be overstated. In her 2004 book, The Goth Bible, horror and dark fantasy author Nancy Kilpatrick wrote, “Propaganda is probably the only subculture publication known to just about every goth on the planet.”

Cover model: Brooke in the role of Dmitri

After a 10-year hiatus, during which I worked as a freelance photojournalist for a number of goth, gay, and fetish publications, Propaganda was resurrected in 2013 on Facebook. Consisting primarily of material from when the magazine was in print, plus some contemporary music and art features, the page has acquired over 28,000 followers. And now, with the advent of propagandamagazine-gothic.com, the legacy continues, offering the dark and decadent delights for which the periodical was famous. Although in this latest incarnation, it enjoys greater freedom of expression than was permissible on the more tightly regulated social media platforms. As for myself, even though I’m not the energetic 25-year-old who launched Propaganda in 1982, I remain firmly committed to conveying its artistic vision to a new generation of the darkly inclined.