A Model Life

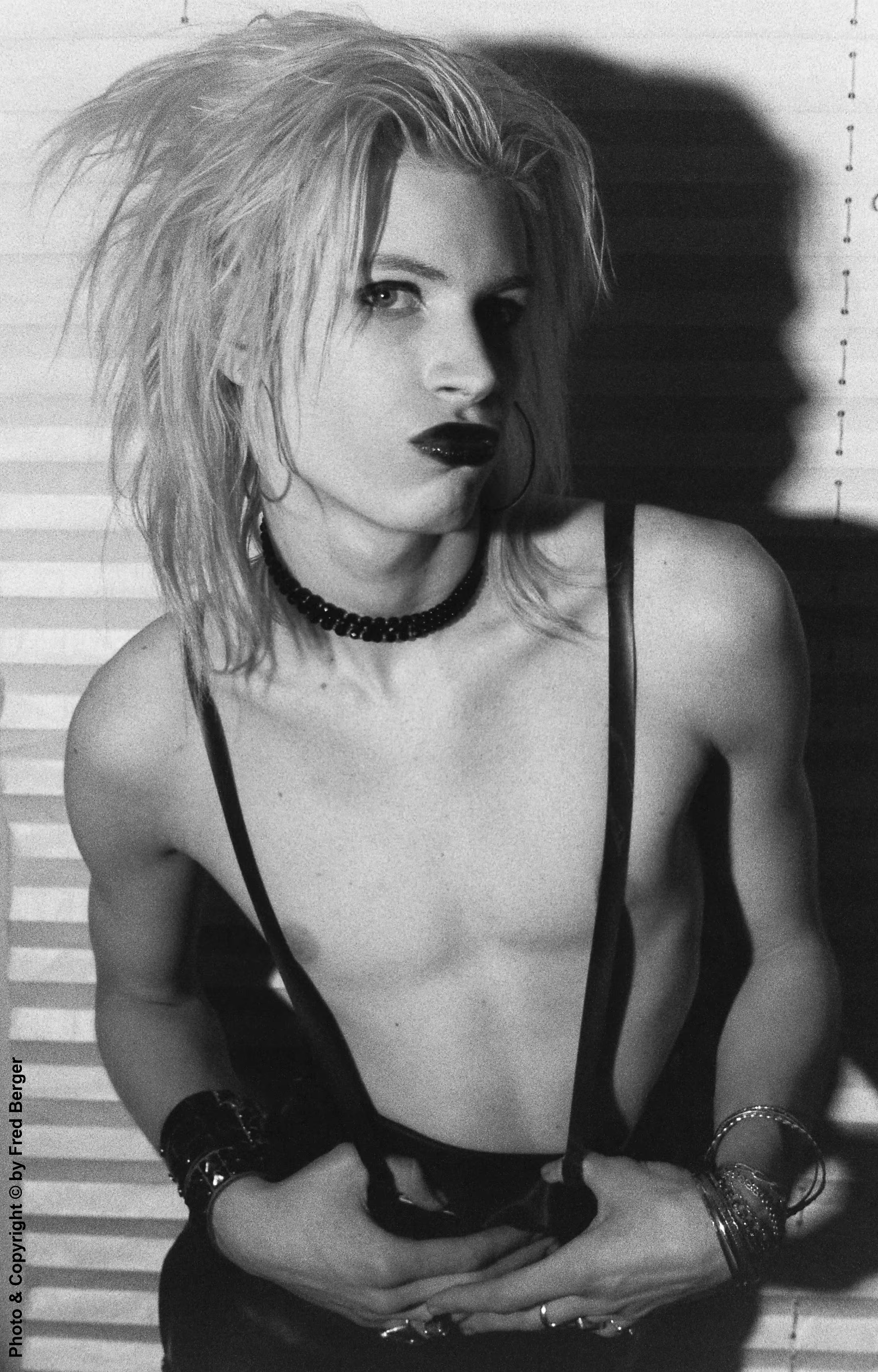

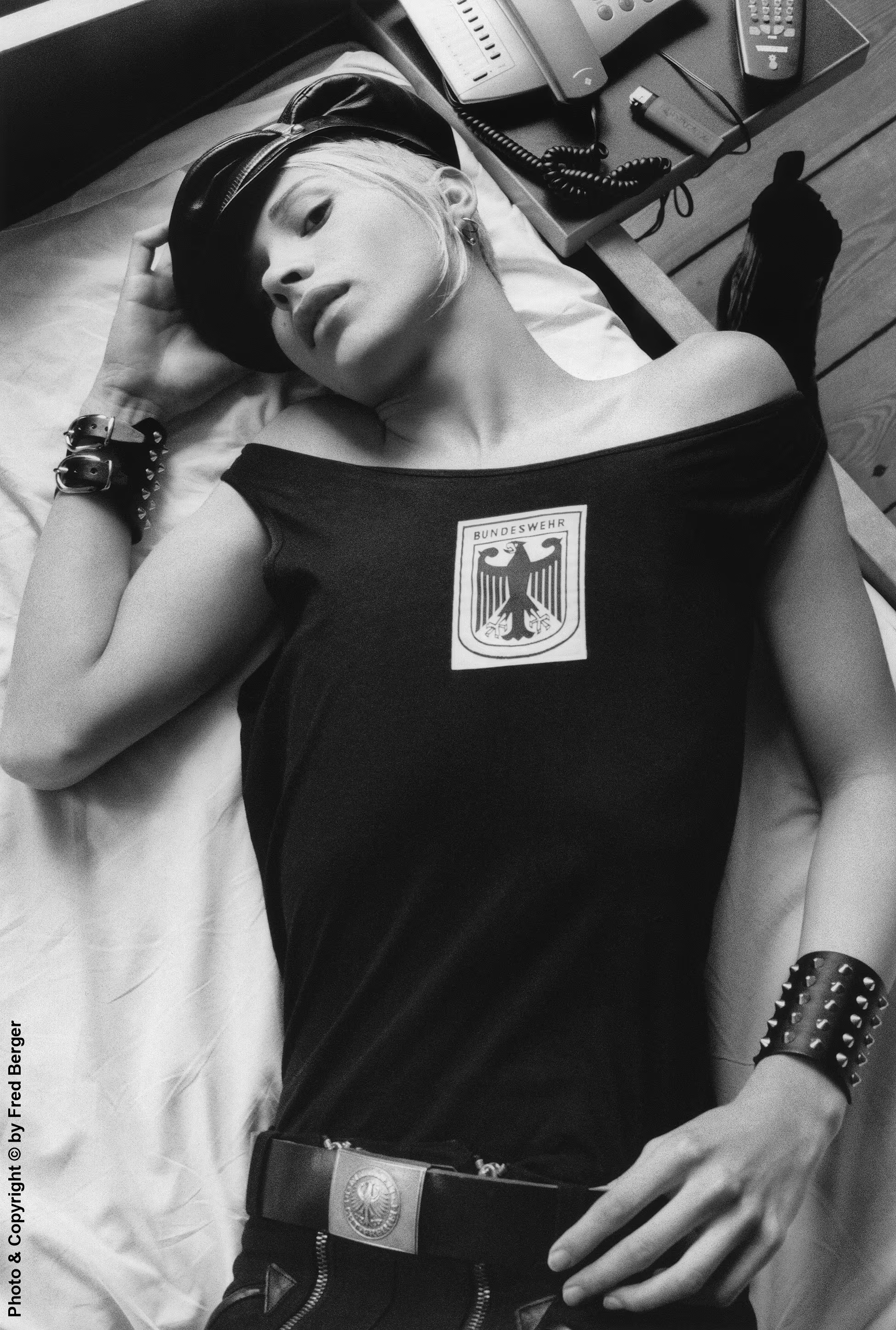

(Photo theme: fetish blondes)

In my college philosophy class, I learned about the works of the 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who is widely known as the “artist’s philosopher” for his emphasis on the arts as a means of achieving transcendence. Aside from the self-denial of asceticism to arrive at this exalted state of being, he viewed aestheticism as equally effective, and more practical for those unwilling to lead chaste and austere lives. Whereas the monk renounces sensuality to attain spiritual purity and bliss, the artist uses it to his advantage in the pursuit of beauty and enlightenment. Lacking either of these methods of copping with the pain and suffering of this mortal coil, we are faced with despair and heartache, hopelessly adrift in a sea of calamities. Of the two paths to salvation within his pessimistic existential framework, I chose that of aesthete, for whom beauty is a virtue of the highest order. And projected through the prism of the human will, which is a preternatural force of incalculable power, an altered state of conscious is achieved for the one who creates the art as well as those who view it, thereby providing mental relief from the woes of the world. Schopenhauer’s synthesis of humanistic and metaphysical doctrines, that made him one of the most influential thinkers of the past two centuries, would provide me with the foundation from which to launch my own artistic revolt against the mundane.

I eventually chose photography as the primary discipline by which I would present the world as I saw it, focusing primarily on its darker aspects, although viewed through a romanticized lens. Stylized melancholy was my preferred motif for interpreting this bleak plain of existence where hardship and strife are the rule rather than the exception. This too falls into the Weltanschauung of Schopenhauer, also known as the “father of modern pessimism,” who held that life is basically meaningless, and that creativity offered at least some hope of coping with this harsh reality. And yet, despite all the skill and determination I possessed, my photographic endeavors would have amounted to little without the incredibly lovely models at my disposal. They were Propaganda’s signature attribute distinguishing it from all other subculture periodicals, causing one commentator to joke that I must have fabricated these fabulous monsters in my laboratory. Ultimately, whether through recommendations and model scouting, or esoteric manifestations of synchronicity and visualization, the discovery of these remarkable beauties resulted in a body of work which was nothing less than iconic. Despite his professed atheism, Schopenhauer himself believed in parapsychological phenomena as a faculty of the Will, a kind of supernatural manifestation of intent and desire.

The visual template by which I operated depended on a sublime alignment of certain physical characteristics starting with the face, consisting of sharply defined cheekbones and jawlines, finely contoured noses, full mouths, and wide-set almond-shaped eyes. Regarding the bodies, delicacy of form was absolutely essential for both male and female candidates, with lean well-defined torsos that invoked a sense of hunger and struggle. If such criteria meant recruiting a relatively high proportion of drug abusers, it was a necessary evil I was prepared to accept, but this had its consequences. Too many of my most popular or promising female models fell victim to overdoses and the ravages of addiction, which interfered with their ability to work. Of my male models who indulged in controlled substances few were side-lined by their excesses, which resulted in a perceived gender imbalance in the magazine’s fashion features and photo essays. But these fetching lads proved to be astonishingly popular by way of their androgynous qualities, specifically slightness of build, juvenescence, and a feminized persona. Whether gothic dandies, cross-dressers, or junkie hustlers, they were the epitome of alternative chic, with many a straight male or lesbian fan confessing that Propaganda’s pretty boys caused them to question their own sexuality.

My most bountiful hunting grounds for potential models were the hip districts of Lower Manhattan, West Hollywood, the French Quarter of New Orleans, Little Five Points in Atlanta, and Hillcrest in San Diego. Here the most eye-catching pedestrians and clubgoers were invariably well acquainted with the magazine, which they held in high esteem for the challenge it posed to mainstream mores and attitudes. Seeming to come from a place beyond good and evil, it existed according to its own values and was answerable to no board of directors, ecclesiastical council, or politburo. It became something of a cliché for fans to give personal testimonies of how Propaganda literally saved their lives by introducing them to forms of artistic expression and an entire community of kindred spirits that liberated them from their isolation and alienation.

This was in a sense the fulfillment of what Schopenhauer claimed was the highest aspiration of aesthetics, which was to reflect the oneness of all through their anguish and sorrow, and in so doing arrive at universal empathy. But with this also comes the inevitable realization that no amount of compassion can free the world of its pain, which I discovered through the disillusionment of my models despite my generosity and courtesy. Some succumbed to their drug habits and personal demons, fated to stints in prison, rehab centers, and psychiatric wards. Three of them died due to narcotics-related causes, and one had a near-death experience from an overdose which resulted in demonic oppression. Other’s retired to a banal and anonymous existence completely divorced from the scene that had given rise to their notoriety. Two of them underwent gender-affirmation procedures and became transwomen, in the course of which they cut all ties to the former identities for which they were renowned. One especially popular model became a devout Jehovah’s Witness in search of redemption, while another entered local politics and buried her Propaganda past to avoid scandal. Of the nearly thirty extraordinary beings who became the face of Propaganda at one time or other, in the end only a handful embraced the experience enthusiastically. Most of the rest, whether ambivalent or regretful, were simply fated to be the beautiful losers they were always meant to be. Life in the counterculture fast lane can do that to a young impressionable person too ill equipped and inexperienced to handle the pressures of being an idol to thousands of fawning fans.

Such exposure also invited harassment from bullies and stalkers, and now with the Internet ravaged by the scourge of cancel culture, they are more vulnerable than ever, especially considering the decadent and controversial roles many of them portrayed. Therefore, to protect their privacy the names of certain models may be abridged, changed, or omitted in the telling of this phenomenal story of creativity and perseverance. However, censorship of Propaganda’s history and fundamental essence is not an option, and these will be faithfully presented in all their terrible splendor. As with Schopenhauer, whose vaunted concept of “the Will coupled with Genius” ultimately failed to overcome the world, I too have discovered the limitations of these faculties in the face of an obstructionist universe. And when anyone suggests that I hold an event for a reunion with my models, I tell them that they’ve been scattered to the winds and are beyond my reach. As it turns out, the model life is not so model after all. But the afterglow of these wayward wonders is enough to take the chill off my bones on a cold and lonely night when I’m in a wistful mood, remembering the heartrending words of the Blondie song “Fade Away and Radiate.”

Content © by Fred Berger

unique visitors